Endpoint selection: a complex process in Clinical Trials

End-users of clinical trials such as clinicians, patients, policymakers, industry representatives, and members of the public generate evidence from randomized clinical trials to guide decision-making in clinical practice and in policy. In most cases, trial outcomes selected for evaluation must address trial objectives, irrespective of their association with the interventions.

End-users of clinical trials such as clinicians, patients, policymakers, industry representatives, and members of the public generate evidence from randomized clinical trials to guide decision-making in clinical practice and in policy. In most cases, trial outcomes selected for evaluation must address trial objectives, irrespective of their association with the interventions.

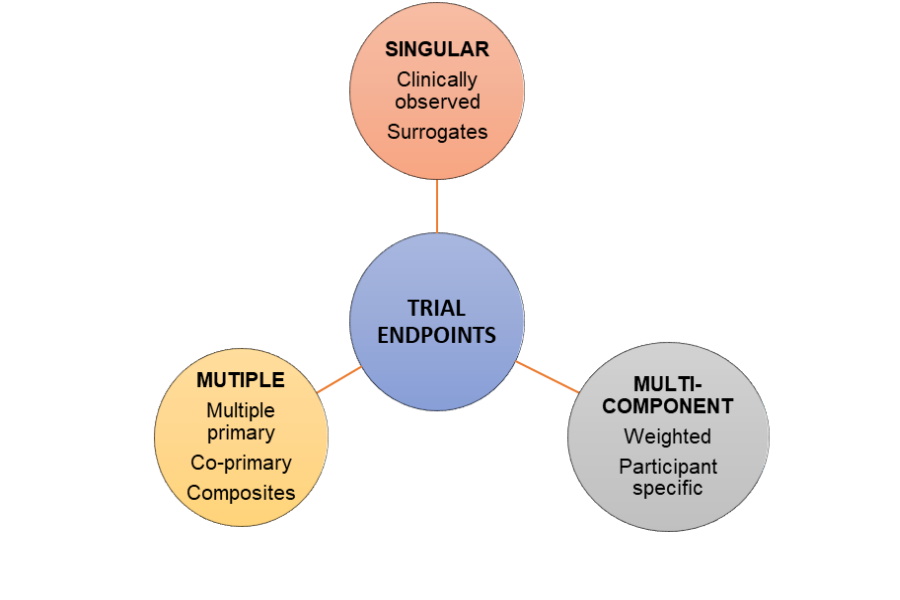

Endpoints are specific measures of these outcomes and their selection is a complex process. Poor selection of endpoints compromises interpretation and implementation of findings, limits evidence generation and diminishes value of research. A single endpoint may not be capable of capturing important effects of an intervention, so multiple endpoints are usually selected.

Manju Bhaskar, Ph.D., CRP

CRA-school Scientific consultant

Generally, endpoints are categorized as primary, secondary and tertiary. The primary endpoint(s) typically measures and addresses the main research question. Secondary endpoints support the claim of efficacy demonstrated by the primary outcomes. Tertiary endpoints typically capture outcomes that occur less frequently, or which may be useful for exploring novel hypotheses.

Classification of trial endpoints

Endpoints for late phase trials can be broadly classified either as clinical or non-clinical. Clinically meaningful outcomes may be measured objectively or subjectively, and are either reported by clinicians, assessed by standardized performance measures, or can be patient-reported or observer-reported.

Non-clinical endpoints, including biomarkers, are measured indicators of a biological or pathogenic process. These include blood tests, tissue fluid analyses, imaging results or physiological measures used for diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring purposes.

Surrogate endpoints are closely associated with clinically meaningful endpoints and can act as their substitutes. A valid surrogate endpoint reliably captures a treatment effect against one or more clinically meaningful endpoints. Surrogates typically capture ‘on-target’ effects based on understanding the causal pathway of the disease process.

An ideal endpoint should be valid and capture the outcome of interest accurately, precisely and consistently with repeated measurements. It should also be measured easily, without additional risk, at low cost, at minimal inconvenience to the patient, and if possible, captured as routine data collection while offering clinical care.

Standardization of endpoints is gaining impetus through the development and adoption of Core Outcome Sets (COS). A COS is a minimum-agreed list of outcomes based on disease-, population- and/or intervention-specific, that should be measured and reported in trials.

Multiple and combination primary endpoints capture the aggregate risk-benefit effect of an intervention. Multiple primary endpoints become ‘co-primary’ if an effect on the multiple outcomes is required to demonstrate proof of efficacy eg: cognitive and functional assessment studies of Alzheimer’s disease.

Composite endpoints may be either composite or multi-component. They are used to aggregate the total benefit when the goal of therapy is to prevent or delay several crucial, but uncommon clinical events eg: death, myocardial infarction, stroke or revascularization in cardiovascular trials.

Multi-component endpoint combines numerous pre-specified component outcomes into a single score, or rating, calculated using a multi-attribute instrument, where the scores for each attribute may be either weighted or unweighted. In contrast to composite endpoints, all components must be assessed for each participant and contribute to the overall score.

Apparently, individual components included in composite and multi-component endpoints are devoid of comparable endpoints. Hence, weighted analysis overcomes this issue, where weights are intended to reflect the relative importance of an individual outcome relative to others. Weights may be assigned by expert judgment, or elicited using either ‘standard’ or ‘revealed’ preference methods.

Weighted composite endpoints are extensively used in the cardiovascular research. Significant heterogeneity exists in individuals with the same disease and similar baseline health states. End-users may want to individualize treatment decisions according to personal characteristics, including disease stage and comorbidities, the availability or lack of treatment options and financial considerations.

Individualized endpoints for participants in a trial may provide a framework for evaluating personally identified risks and benefits. This approach defines treatment success for a given trial participant based on achievable and desirable outcomes depending on their baseline disease status and prognosis. This strategy allows patients to be enrolled into a trial across a spectrum of baseline health and disease severity, with all participants contributing to the analysis.

Optimization and selection of endpoints for clinical trials is an evolving process. Understanding the range of endpoints available for use, together with their strengths and limitations, will help inform end-users while selecting endpoints for late phase trials. There is a need for developing universally acceptable guidelines for optimally selecting and reporting the endpoints emphasizing their significance to suit the participants and address the trial’s purpose.

References:

- S. Kramer, J. Wilentz, D. Alexander, J. Burklow, L.M. Friedman, R. Hodes, Kirschstein, A. Patterson, G. Rodgers, S.E. Straus, Getting it right: being smarter about clinical trials, PLoS Med. 3 (6) (2006) e144.

- US Department of Health and Human Services F, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and Center for Biologics Evaluation and research (CBER): Multiple endpoints for Clinical Trials: Guidance for Industry, 2017.

- McLeod, R. Norman, E. Litton. B.R. Saville, S. Web. T.L. Snelling. Choosing primary endpoints for clinical trials of health care interventions.